In conversation with Sara Hess

Artist and writer Emily Llamazales interviewed Sara on the heels of our recent show with the artists

I’m thrilled to have my friend Emily Llamazales interview Sara Hess on the heels of her recent show, Poems. Sara, Emily, and I were all in school together at UGA, and our paths have continued to cross at odd intervals in the years since. So, having the two of them discuss Sara’s recent work and trajectory feels like a real treat.

Emily is a wonderfully talented interdisciplinary artist and writer whose work draws from science fiction and reimagined biology to address concerns about our ecological future. She was selected as a finalist for the 2023 Emerging Artist Fellowship by Atlanta Celebrates Photography, awarded a 2022/2023 Emerging Artist Award from the Atlanta Mayor’s Office of Cultural Affairs, and received a 2022 Idea Capital Grant (Atlanta). And it seems like now is as good a time as ever to share that Emily will be showing at Blue Boy early next year!

I hope you enjoy their conversation.

Emily: Sara, I've been so fortunate to know you and your work since our time together in undergrad at UGA’s Lamar Dodd School of Art! As I look up at a print of yours above my desk, I realize how much your work has evolved in a physical sense. In this print are the words “Doesn’t need words” floating above a scene of several potted plants, vines, and a squiggly cat tail peeking out from under a table. Can you talk about evolving your art practice, by fusing printmaking with sculpture, and how words have played an increasing role in your process?

Sara: Emily! I love that this print lives with you now—especially in a place where you’re surrounded by words and generating lists in the space between. I still draw my houseplants and cats when I feel stuck. It’s what I know, or, it’s what I think I know. It’s endlessly humbling because once I think I’m completely familiar with the plants and cats that I live with, I begin to pay close attention while drawing and am immediately reminded of how little I actually know about the complexity of each plant or each cat. Drawing has always been at the core of my practice, and lately I’ve been feeling like the writing that happens in my studio has disguised itself as drawing too. I love drawing because it requires slow looking and slow listening. During undergrad, drawing took root in printmaking for me. I was energized by print’s insistence on mark-making (through repetition) and the communal nature of the studios. I made a lot of meaningful relationships in those spaces at the Dodd–we gabbed, shared music, nerded out about print techniques, and tried our best to talk about pretty ineffable stuff.

Over the last three years or so I have become obsessed with locating a sculptural line that I can draw with–to arrange a physical space and to truly be in conversation with the line's environment. For a while, working on a single canvas or stretch of paper stressed me out. I needed material to respond to. I was craving fast-paced iteration and installation. When I felt stuck, I would run to the print studio to make monotypes—working in multiples to build and reveal translucent layers became a generative process for me. This was around the time that I moved to Ohio for grad school. I was building collections of found and discarded materials and objects from public spaces. Like comfort clutter. I incorporated the discarded objects in collages and sculptures, constantly arranging and rearranging them as stacks and systems, like temporary drawings or baby monuments. In hindsight, this process was the equivalent of like, chaotically doing all the chores at once—it was my manic attempt at familiarizing myself with a new city. I was suddenly back in an academic setting and felt like I needed to know and explain my logic for art-making. I was desperate to understand my desire for selection—which objects I kept— and my strategies for organizing and archiving the collections. I’m super grateful for this work because it helped me trust experimental inquiry as rigor. I started asking new questions instead of coming up with answers.

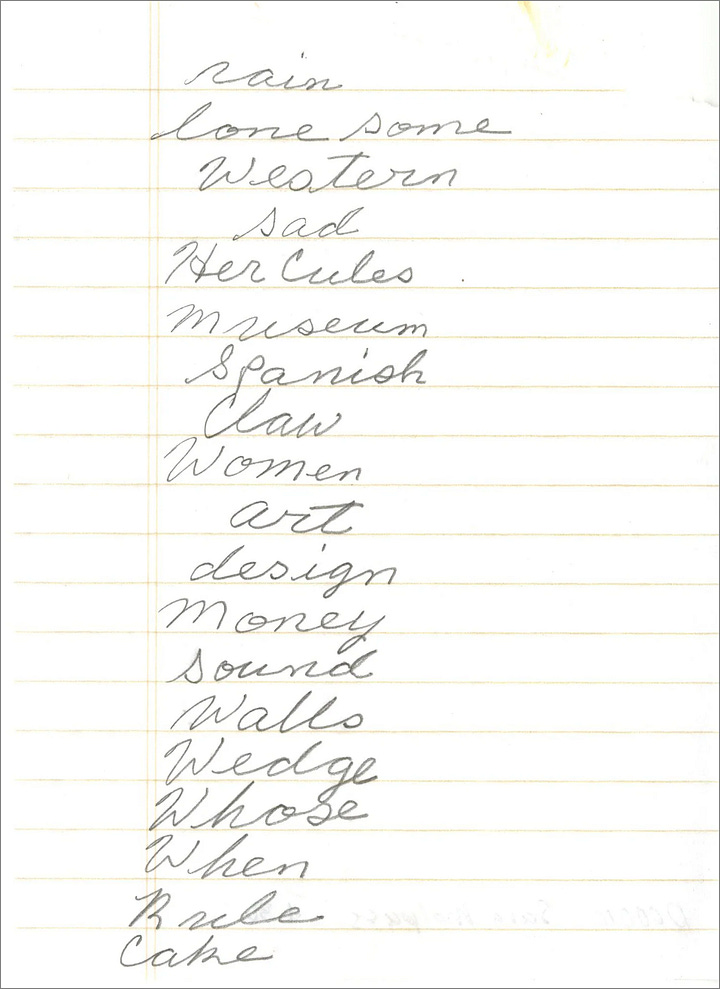

Emily: Within Poems, there's a lot of lists. As an avid list maker myself, I enjoy the process of handwriting tasks and to-dos or making an index of materials around the studio. I’d like to think of these lists as a system of support for my forgetful mind and an aid to my organizational tick. Your sculptures are gestural, lumpy, weighty ,and wordy, and their form really animates them in an approachable way. Most of them require a system of support by way of internal or external armature or maybe they just need to be leaned against a wall. I'd love to hear your thoughts about your list making practice as well as how you’ve been describing your sculptures and your process approaching such large scale objects that need support.

Sara: That’s such a lovely connection you’ve made between these things that require support—our itinerant minds and these wonky sculptures, ha! I love grocery, laundry, and to-do lists. I love to find or read someone else’s list—whether that’s a loved one I live with, a library book’s previous reader, or an unknown Kroger shopper. Found lists are a little window into someone else’s intimate logic, and out of that initial function’s context, they’re deeply poetic. Incidental poems, maybe? Lists not only include ingredients, but recipes too. Developing a new recipe with a strange assortment of ingredients is a metaphor for art-making. Being in the kitchen, the lab, the studio, cooking up concoctions to experiment with... I’m invested in concepts of the domestic within my studio practice, so I find this connection to the space of the kitchen particularly inviting.

Lists also remind me of my sister, my mom, my grandmas, and my great aunt—my maternal lineage—all of whom I am endlessly reminded of in the studio and who I find myself mimicking (mostly subconsciously) in my personal life. Continuing to learn how to know them allows me to trust when it’s essential to channel and when not to channel them through my own actions. Lists are a way in. There’s a reason that I think of friends and family in the context of a list—lists are handwritten and shared. Online DIY craft forums are these collections of recipes too. I learn so many new processes from moms on the internet. Using accessible household materials yields transformative results like the recycled newspaper clay recipe for these clunky sculptures in Poems. Cooking up various ratios of paper pulp is like prepping a pasta, dumpling, or pie crust dough. How will the consistency hold up in the heat? Can the form handle the test of the elements?

Sometimes these sculptures feel and look like pseudo-concrete (maybe especially in relation to the slate floors of Blue Boy), but they are layers of tiny scraps of fragile paper that grow stiff and strong as a collective over time. The sculptures embrace entropy at work, like plants that require assistance and protection to grow using chicken wire or a tomato cage. They’re simultaneously emerging and decaying. I think of them as growths in the gardens during that time of year when everything burns, croaks, and bleaches from the intensity of the sun. They become dormant and transform into fertile compost before returning stronger next season. An accumulation of many small parts transform as a whole, a nod to the invisible systems, labor, and time at work.

Emily: Can you talk a bit about how you and Phillip selected works for the show and how bringing them into the space sort of reanimated them?

Sara: Phillip visited my studio in Athens at the end of the summer. I had just moved back from Columbus, Ohio and this was his first time seeing the work in person after a long winter and spring of email correspondence. We’d been catching each other up since our time in undergrad (at Lamar Dodd School of Art) together. It was mid-February, my last semester of grad school, and the peak of gray Midwest winter. Phillip reached out to tell me that he was building a gallery in his backyard in Savannah! That was such a sweet, bright spot for me, and kind of uncanny too. I remember thinking of Phillip earlier that winter, wondering what he was up to, but he didn’t maintain an Instagram or web presence at the time. I had just installed my MFA thesis show—I felt anxious about post-grad life and I was pining to find my way back home to the Southeast. We continued emailing and texting until my trip down to Savannah in September. After Phillip made his selection, I packed up more than enough work so that we were able to react intuitively and collaboratively curate once in the gallery with Sara Malpass’ work. Sara’s works on paper were the known variable—they’d already arrived from Oakland and were framed by Phillip. The foundation or stakes for us to respond to.

During our morning of install, our conversation totally inspired me—we talked about the film Past Lives and this idea of Sara Malpass and I being from different generations and regions of the country, yet sharing the same name (with no “H”!) and book-ending the timeline of an artist’s life (Sara as a late-career artist recently retired from NIAD and myself as an emerging artist). For me, our works take on a kinship or even a twinning—we leaned into manifesting that sensibility in the gallery. Phillip knew he wanted to include and center the large brown sculpture wrapped in vines called Spoonrest. The relief surface of the paper pulp spells “tell me” in cursive. I was stoked by Phillip’s idea. It allows endless circulation through the space, repeating and murmuring this command. The sculpture is a spoon or shovel-like tool hybridized with the forms of a worm or a pile of compost. The large cavity implies the point of an arrow, which Phillip angled to direct a desired start of a path on the left side of the gallery. The arrangement in the back right corner of the gallery includes an arch and pair of garden gates, which echo a mirror and this kinship between Sara and I’s work. A two-person show immediately developed an intimate dialogue. I think this intimacy is heightened by the domestic space of Blue Boy—the structure itself as a renovated, single carport and its proximity to the alley, yard, garden, and back porch.

Phillip envisioned this left-to-right circulation to guide the viewer’s movement through the gallery. Like a slow, careful reading of a line in Sara M’s lists, then repeating with the second line of the list, and so on. I am honored by Phillip’s curation—weaving this invisible thread of thoughtful partnership. Each sculpture (or cluster of sculptures) has a potential pairing with one of Sara M’s works on paper. The final pair is a soft watercolor, absent of words, but full of purple and green hues and my Iron (for marking impressions), an oversized papier-mâché iron with an image of my Aunt Marge’s kitchen window view (taken shortly after her death) on its underside. My aunt is a major inspiration for my works included in Poems—she was an avid gardener and hoarder; she had no children, but she was a mother. All of these sculptures are part of an ongoing body of work called Psychic Garden, which considers the gut microbiome as a garden and the gut as home to intuition. I’m curious about intuition not as a solo conversation with the self, but as the evolving sum of all the experiences and people who stay with us over time, collected in our gut. Psychic Garden explores intuition as a collective voice, calling on all the women in my literal family, but also, my chosen artist family. These voices manifest as biomorphic ceramics, paper clay, and papier-mâché forms dancing in the garden. I can’t help but wonder what form Sara Malpass’ voice might take.

Emily: And finally, how did you approach the collaboration with Sara Malpass’ works? Were you reacting to them in the process of installing your own works or did the collaboration begin well before then?

Sara: This collaboration feels like a quiet weaving of our respective practices. I first saw Sara M’s work online on NIAD’s website in early spring. I was totally struck by her directness—the earnestness she commanded by taking clear inventory of her surroundings. I immediately saw her desire for drawing and I recognized her deep investment in list-making and cursive script. A shared affinity observed and felt in the record of her hand. What a special way to get to know someone. I think of cursive as a longing continuous line, constantly shaping and shifting on its own. Cursive is super malleable and possesses a unique kind of legibility. It can be read, but it can also be felt. This line is also vulnerable, easily abstracted by compression or stretching. Most of my sculptures are coated in layers of looped lines using pressed paper pulp and yarn—spilling and spelling short phrases and poems. I also sculpt cursive porcelain and ceramic text, embracing the fragility of the single coil of fired clay, sourced from dirt of the earth, transformed to stone, like a humble monument for someone.

I like to imagine my Great Aunt Marge at my age, and I love to imagine what it would be like to hang out with her as my contemporary, especially the older I get. Drawing is great for this—imagining speculative futures or re-imagining the past. It has been such a joy and privilege to learn and think about Sara Malpass, through her work, through Phillip, and through NIAD Art Center. I now imagine what it would be like to hang out with Sara, to riff in the studio together, as we are right now, each at my age, both at her age, or perhaps in another life.

A few last announcements

I am so beyond excited to share that Sara & Sara’s show will take on a second life in the new year at Whitespace in Atlanta. I’ve been familiar with and loved Whitespace’s programming for years, and it means so much to be invited to bring this show to their beautiful space.

I will share more details soon; stay tuned!

Opening on December 14th

Our next show, One lifetime is enough to learn life’s preciousness, will open on December 14th with work by Dani Rodrigues (Bogota, Colombia) and Kate Burke (Atlanta, GA). There will be a reception that night - I hope you can make it!

Loving this!

What a great insight to the art process! And how our lists are a window to life- love finding lists my parents made, it feels so personal. Thanks for a great conversation!